Barriers to Equitable IBD Care: Racial Differences in Healthcare Utilization Across the Lifespan

By Lauren DeSouza- Master of Public Health, Simon Fraser Public Research University – Canada

https://www.qbhinc.com/our-team/

Staff Research and Content Writer

© Copyright – SUD RECOVERY CENTERS – A Division of Genesis Behavioral Services, Inc., Milwaukee, Wisconsin – August 2025 – All rights reserved.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, affects more than 3 million Americans. Although IBD is more common among White Americans, patients from other racial groups often face greater barriers to care and worse health outcomes from IBD.

IBD is a lifelong condition that can begin in childhood or adulthood. It places a heavy burden on patients and the health system, with average out-of-pocket costs of about $9,000 per year for medications, hospital visits, and surgeries. With no cure, IBD can cause disability, stigma, and serious, even life-threatening, complications.

Consistent, timely care is essential to prevent flare-ups and avoid emergency department visits. Yet barriers such as limited access to medications or specialists lead to worse outcomes. Previous research shows that Black and Hispanic Americans face greater challenges accessing IBD care and rely more heavily on emergency services compared with White Americans.

A new nationwide study aimed to compare healthcare utilization among patients with IBD across racial groups in childhood and adulthood. The study’s results can inform future efforts to reduce barriers to care and improve health equity among patients with IBD.

Photo by Sora Shimazaki via Pexels

What did this study do?

In this study, researchers used data from two national administrative databases, Optum’s deidentified Clinformatics Data Mart Database (CDM) and Medicare, to compile one of the largest cohorts of IBD patients in the US. The researchers were interested in understanding how race impacted healthcare utilization for IBD patients. IBD patients were categorized as having Crohn’s Disease (CD), Ulcerative Colitis (UC), or IBD not otherwise specified (IBDnos).

Based on the data from the two databases, the researchers categorized racial groups as White, Hispanic, Asian, or Black. While both databases had “other” categories, the researchers excluded this category from their analysis due to heterogeneity.

The researchers measured healthcare utilization using medications dispensed, outpatient encounters, emergency department encounters, hospitalizations, surgeries, and lower-endoscopy and cross-sectional imaging.

The researchers performed statistical analyses for 3 age categories:

- Children under 20 years

- Adults aged 20-64 years

- Older adults aged 65 and older

In their analysis, the researchers compared healthcare utilization for each racial group, using White patients as the reference group. Since the researchers ran many statistical tests for each age group and race, they used a secondary threshold to determine statistical significance and avoid false positives. For a value to be considered statistically significant, the p-value of the odds ratio had to be less than 0.05, and the false discovery rate (FDR) had to be less than 10%.

What were the key findings?

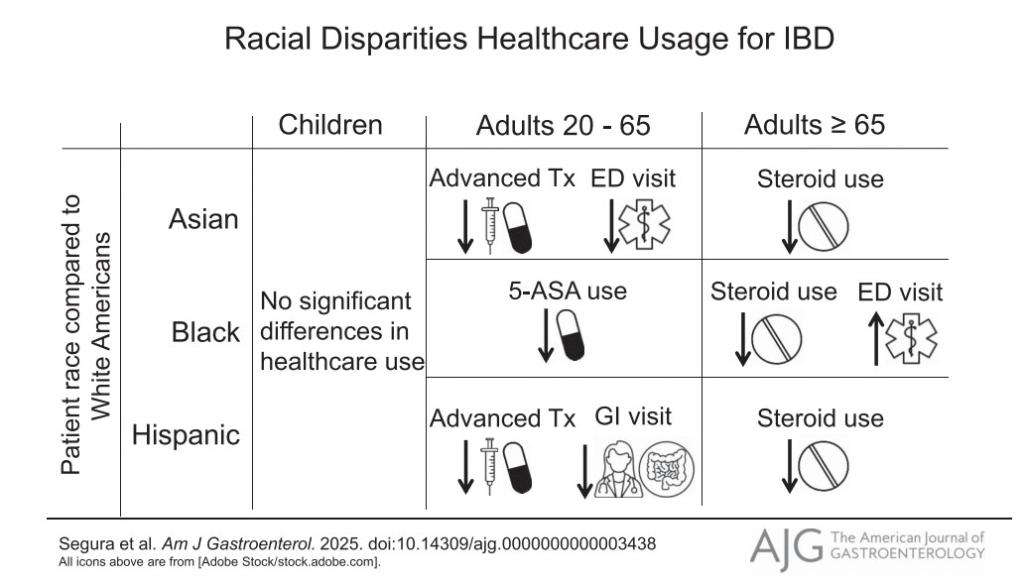

The below graphic is taken from the study and illustrates the study findings across the 3 age groups and racial categories.

Children (<20)

Overall, Black, Asian, and Hispanic children did not have significant differences in healthcare utilization compared to White children.

The study found the following differences:

- Hispanic children had more endoscopies and imaging than White children

- Black children visited a gastroenterologist less than White children

- Asian children visited a gastroenterologist less than White children and were treated with less advanced therapies.

However, none of these observed racial differences were statistically significant. When the researchers added more variables to their models, the associations became stronger (especially for differences between Hispanic and White children). However, the results were still not statistically significant. The authors note that only a small portion of the study population included children, so it is possible that these trends would be statistically significant with a larger study population.

Adults (20-64)

Clearer racial disparities emerged among adults. Relative to White Americans, Asian and Hispanic adults used fewer healthcare resources for IBD management. There were no consistent differences in treatment patterns when comparing Black and White Americans, although Black Medicare-eligible beneficiaries were more likely to use the emergency department for IBD-related issues.

- Hispanic adults were treated with less advanced therapies and fewer steroids than White adults. They were also less likely to have seen a gastroenterologist or to have had a lower endoscopy. However, they were more likely to have received intravenous iron.

- Black adults were more likely to receive steroids, use emergency services, and require hospitalization for IBD than White adults. However, these differences disappeared after controlling for socioeconomic status.

- Asian adults were also treated with less advanced therapies than White adults, but were given more intravenous iron.

Older Adults (65+)

There were significant differences in steroid use and emergency department visits among older adults. Some differences disappeared after controlling for socioeconomic status.

- Hispanic older adults had less steroid use than White older adults.

- Black older adults had lower steroid use and higher use of emergency department care than White older adults.

Asian older adults used fewer steroids and received fewer advanced therapies and immunomodulators than White older adults. Theyalso visited the gastroenterologist less frequently.

What do these findings mean for racial equity?

The results of this study indicate progressive healthcare disparities for racialized patients with IBD across the lifespan. Disparities in receiving advanced therapies, screenings, and steroid use could indicate lack of knowledge among patients, lack of affordable treatments, or lack of access to a knowledgeable IBD specialist, all of which are underpinned by racial and socioeconomic inequalities.

There were observable differences in healthcare utilization for Hispanic children with IBD compared to White children. Hispanic children were more likely to receive diagnostic endoscopies, imaging, and glucocorticoid treatment than White children, which could suggest a trend of more serious or complex IBD cases among Hispanic children. However, none of these results reached statistical significance, possibly due to a small sample size. The authors emphasize that more research is needed among children with IBD to determine if racial differences in treatment exist.

Among working-age adults (ages 20-64), clear differences were seen between Black and White Americans and between Hispanic and Asian Americans and White Americans. Black adults initially had higher steroid use, more hospitalizations, and more emergency department visits compared with White adults. However, these differences disappeared once the researchers controlled for socioeconomic factors such as location, comorbidities, income, and specialist visits. This suggests that racial differences in healthcare utilization between Black and White adults are attributable not just to race, but to socioeconomic disparities between Black and White adults that result from structural racism.

Asian and Hispanic working-age adults had lower utilization of IBD care compared to White adults across all models. The researchers hypothesize that immigration-related factors could explain some of these differences; for example, immigrant communities can face language barriers, financial hardship, or discrimination that make it difficult to access health care. They may also face stigma or shame around discussing and seeking treatment for a bowel disease. Finally, certain cultures, especially among Asian Americans, may prefer to use Eastern (alternative) medicine instead of Western medicine.

Finally, among older adults (age 65+), Black adults were more likely to use emergency services for IBD and be given fewer steroids than White adults. The other observed differences weakened after controlling for income and insurance status. Higher utilization of emergency services suggests a lack of care to prevent IBD flare-ups and emergencies from occurring, which the authors suggest could be due to structural and institutional racism, lower health literacy, and higher out-of-pocket costs for treatments.

Disparities in care among Black working-age adults may set the stage for worse outcomes later in life. Because many of the observed differences in steroid use, hospitalizations, and emergency visits among Black adults aged 20–64 could be explained by social and economic factors, this suggests that barriers such as limited access to specialists, lower income, and systemic inequities reduce opportunities for consistent, preventive IBD management. Over time, these care gaps can accumulate, leading to more uncontrolled disease and higher reliance on emergency services as Black adults age. This helps explain why, in the 65+ group, Black adults had significantly higher use of emergency care for IBD despite controlling for many clinical and socioeconomic factors.

Photo by Muskan Anand via Pexels

Key Takeaways: IBD Care Across the Lifespan

This study suggests that differences in IBD care by race exist in the US, but many disparities can be linked to social and structural factors rather than race alone. All non-White racial groups faced social and structural barriers to accessing and using health services for IBD, but there were notable differences between age categories. Hispanic and Asian adults tend to receive less chronic IBD care, Black adults have higher emergency care use (especially when older), and Hispanic children may receive more procedures but not advanced therapies. Social determinants like income, insurance, and health literacy play a significant role.

Photo by Towfiqu barbhuiya on Unsplash

Looking across the lifespan, the findings suggest that disparities in IBD care begin early and evolve over time. In childhood, differences may reflect more complex disease recognition without equivalent access to advanced therapies or specialists for racialized populations. In working-age adults, socioeconomic and immigration-related barriers shape ongoing management and access to specialized care. By older adulthood, cumulative inequities contribute to greater emergency service use and reliance on acute care, especially among Black older adults. Together, these patterns point to missed opportunities for early intervention and equitable, long-term management of IBD across all racial groups.

Looking across the lifespan, the findings suggest that disparities in IBD care begin early and evolve over time. In childhood, differences may reflect more complex disease recognition without equivalent access to advanced therapies or specialists for racialized populations. In working-age adults, socioeconomic and immigration-related barriers shape ongoing management and access to specialized care. By older adulthood, cumulative inequities contribute to greater emergency service use and reliance on acute care, especially among Black older adults. Together, these patterns point to missed opportunities for early intervention and equitable, long-term management of IBD across all racial groups.

These findings underscore the need for efforts to improve access and quality of IBD care for historically marginalized populations. Addressing these disparities will require not only clinical awareness but also policy reforms that expand equitable access to care, reduce financial barriers, and invest in community-level interventions for populations historically excluded from specialty IBD care. Finally, further research is needed to inform future healthcare and policy interventions that eliminate racial disparities and achieve health equity among all patients with IBD.

Main Points

- Although IBD is less commonly diagnosed among patients of color, they access IBD health services at significantly lower rates than White patients.

- All racial groups (Hispanic, Black, and Asian) had lower healthcare utilization than their White counterparts across the lifespan.

- Disparities in IBD care begin in childhood and persist across the lifespan, leading to worse outcomes in older adulthood (e.g., higher emergency department use).

- Differences in healthcare utilization for patients with IBD are driven not only by race but also by socioeconomic and immigration-related barriers, which may be underpinned by structural racism.

- Addressing social determinants such as income, health literacy, stigma, and access to specialists is essential to reduce disparities and improve outcomes for patients of color with IBD.

References

Segura, A., Brensinger, C., Pate, V., Siddique, S. M., Parlett, L., Hurtado-Lorenzo, A., Kappelman, M. D., & Lewis, J. D. (2025). Association of race and ethnicity with healthcare utilization for inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: A retrospective cohort study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000003438

Burisch, J., Claytor, J., Hernández, I., Hou, J. K., & Kaplan, G. G. (2025). The cost of inflammatory bowel disease care: How to make it sustainable. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 23(3), 386–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2024.06.049